Understanding Child Psychology for Youth Coaches: A Practical Guide to Smarter Training

“Knowing reality means constructing systems that correspond to reality.”

I know what you might be thinking, ‘I’m just a football coach. I don’t have the time or energy to study psychology in my free time.” Well, this article is for you. It’s aim is to provide a quick, convenient, useful guide for any youth coach to learn the basics about child development, alongside a free handy PDF guide with tips for how to plan successful training sessions.

In her article on child development for the Washington Post, Jenna Gallegos writes, “Decades of scientific studies have shown even an immature brain is capable of extraordinary feats. Yet a fully developed brain is necessary for actions that adults take for granted, such as risk assessment and self-control.” And perhaps, this leads to our gravest error in youth football coaching: we sometimes fail to see that children, no matter what they can produce, are still children. Yes, they might be capable of the extraordinary, but their brain is still figuring out the ordinary.

Children Aren’t Mini Adults

As a youth coach, having a basic understanding of child development allows you to have a deeper comprehension of what’s going on in your player’s minds and in the process empathize with them more. When we apply this knowledge to our session plans, we make certain that we don’t ask a young player more than they are cognitively capable of. This is paramount to their player development.

Jean Piaget, a pioneer in child development psychology, was fascinated with the minds of children and more importantly, how adults misperceived them. In his early work, he noticed that children up to the age of twelve were having difficulty with certain intellectual tasks that adults assumed children should have been able to do. He believed that the difficulty seemed to be ‘the child’s inability to relate adequately the parts of the problem to the whole’. He came to the conclusion that logic is not inborn but develops little by little with time and experience. This was the basis of his child developmental theories.

Piaget’s work gave way to the psychological theory and educational approach called Constructivism. Constructivism considers that we are continuously creating our own comprehension of the world by reflecting upon past personal experiences. This process helps children develop ‘schemas’ or mental models to interpret the world more easily. For Piaget, children who were able to create these mental models and correctly use them in the right context displayed what we would traditionally call intelligence. Piaget wanted to change the thinking that children were ‘tiny humans’, but rather that they were constantly developing in every possible way.

Read: The Language of Football

Although this may seem obvious to us, I believe that when interacting with children adults tend to forget this from time to time, often during stressful situations. In most cases, especially in the field of youth sports, people acknowledge a child’s physical limitations but fail to discern their cognitive limitations. Perhaps it’s because we cannot see how underdeveloped their cognition is, whereas we can see their underdeveloped physical qualities. When working with children that is a grave error.

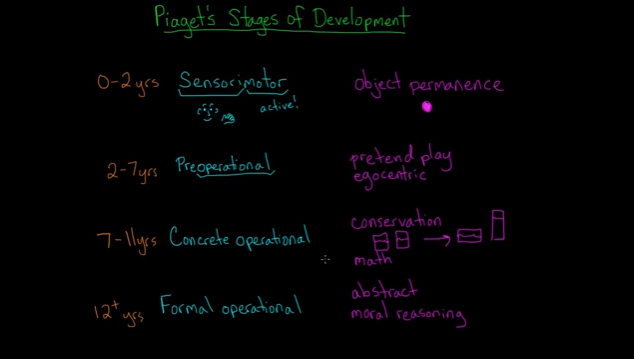

A great place to start with understanding child development psychology is with Piaget’s Stages of Development. The following image comes from the highly resourceful Khan Academy. If you have time or interest, I’d encourage you to check out the full YouTube video

What They See Isn’t What You See

This serves as a general overview of the different divisions in cognitive periods Piaget made, although the ages are not rigid and can depend on the child.

The following two videos give some examples of the development of logic with age.

The first video shows a young girl, Emmanuelle (three and a half years old), being asked to simply copy a triangle. What she draws is certainly not a triangle but in her eyes she has copied it perfectly. She even calls attention to the corners of her shape, referencing the corners on the triangle as well. Her perception is different than ours, and serves as a good example of why younger players may not perceive things on the pitch in the way that we expect them to.

Similarly, the manner in which a child solves a problem or deduces something may not align fully with our expectations as adults. At times, when we see a child trying to work something out our first instinct is to do it for them or show them how it’s done, which is a serious mistake on the pitch.

As you will see in the second video, depending on their ages, children will work a problem out and deduce a solution through their own distinctive manner. If you have time, I’d encourage you to watch the entire eight minutes of the experiment. Watching the children of different ages work out how to sort the sticks by size shows us that although they may go about it differently, they all succeed.

I’m drawn to the exercise at the 6:30 mark, when four year old Renaud is asked how many sticks are larger than the smallest. He counts them and gives the correct answer. However, when asked the same question about the biggest stick, but with all the sticks except the biggest one covered, he is incapable of answering. Piaget comments, “…even though the answer is obvious to us.” And that’s exactly why I wanted to show these two examples. What’s obvious to us, maybe isn’t obvious to the children we are working with, and as coaches our job is to understand this, and not to get frustrated with our young players.

Coaching Smarter by Coaching to the Brain

Luckily for us, there are many resources out there which have used child development psychology and applied it to sports. In the process of writing this article, I did a fair amount of research, as well as scouring my UEFA course notes, and found some fantastic scientific publications on the subject. I’ve created a practical PDF which organizes information by ages, their characteristics, and how best to coach each age.

For example, during the infancy stage children typically lack the ability to think hypothetically. Knowing this, we would avoid speaking to a player about what could have happened had he or she acted differently. Generally before the age of 10, children also lack the ability to think abstractly. Therefore, they struggle with concepts such as space and time. They simply don’t have the mental models about such notions to relate to their world. Taking this into account, we wouldn’t expect our players to perfectly understand the spatial relationship between themselves and their environment. We might assume that their mistakes are because they aren’t good enough or they aren’t looking around but in fact it’s because cognitively they see the space differently. Just like Emmanuelle saw the triangle differently.

During adolescence, we know that teens tend to be self-centered. Although this may seem like a negative behavior, as we can see in the chart, that egocentrism can manifest as self-motivation.

In the charts I’ve created, you’ll find a section for each stage of development called ‘Coaching Approach’. I believe for this to be the most important and practical part of the tool. It gives you some guidelines to follow to adjust your instructions, feedback, the player’s motivation and how that all relates to the activity. For example, let’s imagine that you are in charge of an under-11s boys team. When creating your training exercises you can go down the list and check whether the exercise is fun oriented, if it simulates the game, and if it has unplanned reactions to stimuli. Then you can think about the feedback and correction you give your players, and the same about how you instruct your players in training sessions.

This table is just the tip of the iceberg of what can be done with child development in sports. I have been lucky enough to work with and see firsthand clubs which have created training methodologies where there are clear guidelines for each age group in terms of what cognitive or physical abilities each player should have at every level. This type of organizational clarity would be impossible without the knowledge of child development psychology.

This is what the most successful academies in the world do so well. La Masia, F.C. Barcelona’s storied academy, have very clear, and what some would consider strict, age markers that indicate to the club whether the player is progressing within the Barcelona methodology. These kinds of training methodologies are highly systematic and are based on the Constructionist learning methods discussed earlier. Simply put, they strictly adhere to the old adage, ‘You have to learn to walk, before you can run.’ What technique is necessary to walk? What cognitive elements do you need to be capable of to begin to run? Beginning to think like this, clubs create successful academies which will produce cognitively, physically, and emotionally capable players.

Your Role Isn’t to Teach Like Pep

With that said, none of this is possible without the coach believing in the system, and in my humble opinion, that is where everything falls apart. This requires forgetting about the result at the weekend, and frankly, often coaches are selfishly not willing to do that. This training approach revolves entirely around the learner. Coaches should understand that they are coaching to develop their team’s age specific cognitive abilities, and not to play like Manchester City. They are not Pep Guardiola. They do not have millions of pounds to spend in the next transfer window. Their team is never going to play City’s positional play system. And. That’s. Okay. They are 12 years old. They need to develop mental models to better their spatial awareness. They need to improve their bilateral movements. They need to become comfortable with their ever changing body.

Coaching is very simple. Teach them what they can learn, do not teach them what you want to teach them. A coach’s job is to analyse their team’s emotional, physical, and cognitive capacities and help them create new mental models which they can use to relate to the complex nature of the sport a little bit better every year. It’s about them, not you. So let me repeat that; Teach them what they can learn. With some basic knowledge of their brain development, you can adjust expectations, thus preventing frustration. Through this process, you will have more compassion and understanding with your players, ultimately giving way to your development as a coach. And perhaps that’s where we must begin the youth sports revolution. Not with the overhauls and major changes from our federations but with our own self-improvement.

“And once I knew I was not magnificent...I could see for miles and miles and miles.”

When I began, It’s Just a Sport I wanted to be able to give coaches practical tools which they can use to improve. I feel that this guide perfectly serves that purpose. I’ve tried to trim all unnecessary information whilst maintaining the science behind child development psychology.