Positional Play: Crash Course Part 4 of 4 - Generating Superiorities

“The team’s movements create the mobilization and the imbalance of an opponent, and most importantly, the exploitation of said imbalances.”

What is your intention? What is the purpose? What is the aim, the objective? These are all questions a coach should be asking themselves on a regular basis. Why am I doing this? We don’t go out to a training session, scatter some cones about, give the players a couple of footballs, and expect them to play better at the weekend. This is simply irrational thinking and if it were done in any other discipline, it would be questioned immediately. If a teacher showed up the first day of school and gave the students a list of vocabulary words with no context, parents would question their methods. As with all educational fields, football requires a purpose, an end to justify the means. If the previous three parts of this positional play series were the means, this part is the end.

In part 2, we examined the team structure required to create the right conditions for the group. In part 3, we scrutinized the spaces created by the structure and within those spaces the interactions which arise among players. In this part, we’ll study the superiorities that will come as a result of executing all of the aforementioned elements. These numerical, positional, and qualitative advantages are the fruit of positional play, and ultimately will be expressed collectively in matches.

Superiorities

When we talk about being superior or inferior, most people tend to directly go to the quality. We associate being superior with being better, although to be better is in and of itself meaningless, and we must be more specific. In the same way, when we consider these superiorities, we must specify how they are giving us an advantage over the other side.

Paco Seirul•lo, along with many other brilliant coaches who delve into positional play, classifies superiorities into four categories: numerical, positional, qualitative, and socio-affective. For the purpose of restricting this article to the tactical aspect of the style, we will exclude socio-affective superiority. That isn’t to say it’s not important, on the contrary, it’s highly significant to the social aspect of the game, and for that reason it requires an entire post about it apart from this one.

Numerical

As the name might lead you to believe, numerical superiority refers to the amount of players in a given zone or space. In my opinion, this is the simplest superiority to identify in a match. It requires no context as it can be distinguished from a screenshot at any given moment of a match. Creating it on the other hand is much more difficult and calls for correct positioning along with each player meeting their responsibilities which we discussed in part 3.

Obviously, football is played with eleven players on each team, therefore in theory there should never be numerical superiority. Although, due to the laws and regulations of the game, the defensive team always tries to protect their goal, consequently placing more players in their defensive third in order to protect their goal.

Let’s imagine in a match both teams are using a traditional 4-4-2, and each player plays in their given position. The back four stay their defensive third, the midfielders stay around the middle of the pitch, and the two strikers stay further up the field. If both teams played this way, the two strikers would always be outnumbered and the midfielders would always be in numerical equality. The result of such a situation would most likely be one of the most boring matches you’d ever seen.

Thankfully for us, football’s pioneers devised plans and tactics that deviated from these traditional ways of playing and realized they could move players around and position them differently in order to break the continual numerical inferiority and equality. Breaking the field of play into zones, and in those zones breaking the sequence of events into small sided games, they were able to see that teams could create 2v1, 3v2, 4v2, with the purpose of progressing up the pitch.

Read: Positional Play in Motion

Let’s take the build-up from the defensive third. Firstly, the goalkeeper needs to participate and be considered a field player just like anyone else on the pitch otherwise, the team in possession will always be, in the best case scenario, in numerical equality. Secondly, as we’ve learned, the center backs must dribble to attract a defender, to draw them out. Synchronously, another player, preferably a midfielder must support the ball possessing center back. These two players have just created a simple 2v1, and if executed correctly, they should be able to progress up the pitch. The following image depicts the situation.

This is just one way that a team can create numerical superiority, furthermore, this advantage can occur anywhere on the pitch. As you can see in the following video, numerical superiority can happen anywhere and will involve different amounts of players.

Video of Numerical Superiority

Positional

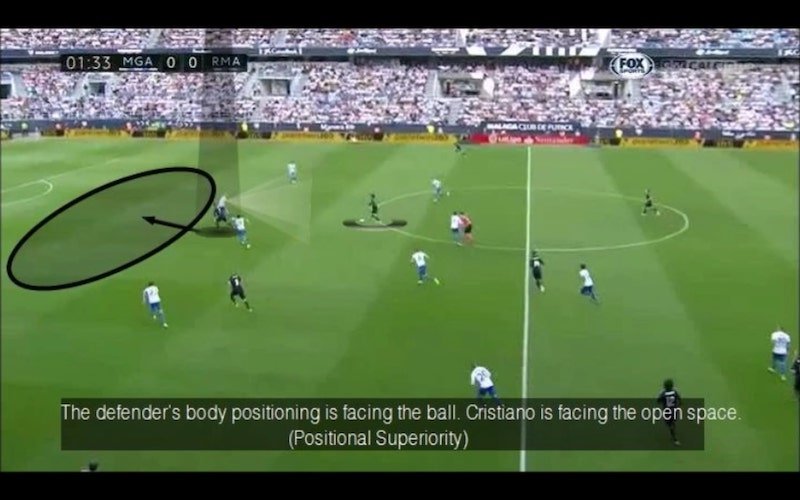

Positional superiority is slightly more difficult to identify, and requires more context within the match. To phrase it simply, to have a positional advantage is to be better positioned than the opposing team in order to achieve an objective.

Offensively, the objectives are to maintain possession, progress up the pitch, and ultimately score a goal. Defensively, a team wants to regain possession, negate any opposing progress up the field, and deny any goal scoring opportunities. From this perspective, positional superiority would be to situate oneself to give oneself an advantage in meeting one of the previously mentioned intentions.

This can be done through several individual techniques. The most common one being body orientation, that is to say, the way that a player is facing, not only their eyesight but their hips. Every coach knows whichever way your hips are facing is the direction that you are going to take your first step. Yes, you can run backwards and sidestep, but if you are going to run with speed your hips need to be facing the direction that you are going to run. For this reason, body orientation is crucial in positional play.

Strictly speaking, as an attacker, knowing which way the defender is facing is essential in gaining valuable milliseconds that make the difference between scoring and not. As you will see in the video, the attackers create a positional advantage through the exploitation of the space behind defenders, the space that the defenders are not looking at because they are either focused on the ball or another attacking player.

Video of Positional Superiority

Along with body orientation, there are other ways to achieve positional superiority. For example, the trajectory of supporting runs, checking or breaking, influence the positional advantage heavily. As coaches, we’ve all taught our players that they should be making curved runs into the penalty area, but I’m sure that most coaches have never wondered why. It’s for exactly this purpose. To try to meet a cross perpendicular is much more difficult than to meet it almost parallel via a curved run.

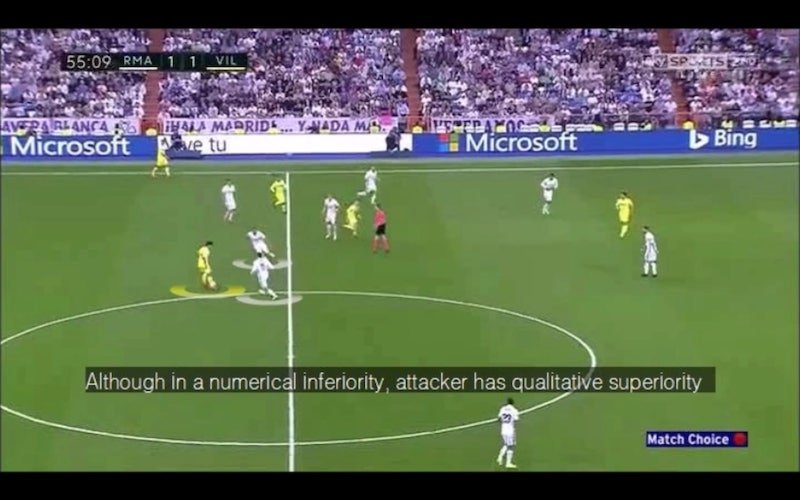

Qualitative

Qualitative superiorities are the advantages that require the most context and specific understanding of players’ skills. In order to be able to correctly identify this superiority, one must know exactly what each team or player does well or poorly. To put it simply, it’s when one player or group of players are better than their direct opponent.

Imagine a 1v1 between a very skillful winger and a slow, clumsy center back. Most likely the winger would get past the defender nine out of ten times. This is the premise of qualitative superiority: the knowledge that one player will be better than another in specific moments of the match.

Angel Cappa, the legendary Argentine manager, said, “A team with a good collective idea but lacking skillful players, they can’t be champions. However, a team with very skillful players but an awful collective idea, it’s possible for them to be champions.”

Qualitative superiority can explain this phenomenon. If you have a skillful team, who are constantly putting themselves in situations of numerical and positional inferiority, through qualitative superiority they can achieve the objective.

Read: Messi: The Master of Space

We have seen this many times when Messi, Cristiano, Pele, Maradona, Zidane, Ronaldinho etc, seem to be in situations where it’s unfathomable they will find success, yet they manage to break out magical moments and succeed. This is qualitative superiority.

Video of Qualitative Superiority

Of course, you are most likely never going to coach talent like the players I’ve mentioned, but that doesn’t mean you can’t create this type of advantage on the field. It’s just a matter of having a clear understanding of your players’ skill sets and exploiting them. For example, if you have a winger who is masterful in one versus one situations, then you might create an overload on the opposite side to isolate him and let him prosper once you get him the ball. Maybe you have an extremely tall striker; you might play in the wings and look to find him in the penalty area even when he is outnumbered.

Not only can this be done to accentuate your players’ strengths, but you can look to pinpoint the opponent’s weaknesses. Along the same lines, you might look to attack the center back who lacks speed, or force the opposing team to play in the air when they lack in that department. It’s just a matter of analyzing and exploiting the advantages.

Free Man

This crash course to positional play wouldn’t be complete without introducing the concept of the free man.

The Catalan midfield maestro, Xavi Hernandez, once described the concept of the free man using a tactic that Pep’s Barça utilized frequently.

“To look for the free man is, for example, the center backs have the ball and one of them is always free because you always have more defenders than strikers. In this case, Puyol dribbles up with the ball until an opponent steps up to him. If my mark is the one that tries to stop him, then I become the free man. If Iniesta’s man steps up to him, then Andres becomes the free man. And like that we look for superiority in any area of the pitch. You create three versus two, you win it, and now you have a free man. We advance up the field.”

In that short passage Xavi depicts how the previous superiorities are the cornerstone to this concept. Creating a three versus two situation is clearly numerical superiority. Positioning themselves behind their marks in order to progress demonstrates positional superiority. And although qualitative superiority isn’t specifically mentioned, we know that the quality those three players possess obviously exemplifies qualitative superiority.

Training

Now we’ve arrived to the practical aspect of this course, the part where we must discuss how to relate all of these concepts into a training session. You might have the urge to go back to your team and regurgitate all of positional play’s notions but this wouldn’t benefit the players. Football is a skill that is acquired over time and as with skills acquisition there are several steps that must occur before the skill set is fully assimilated and is able to be performed naturally.

Firstly, the player must have the awareness to identify all of these topics in real time. That is to say, they must have been immersed in hundreds and thousands of match situations which required the knowledge of positional play. It’s important to mention that they may not consciously know the concepts we’ve discussed, nevertheless, through correct implementation of training sessions which mimic a real match and the circumstances it entails, they’ll know what to do in each predicament they encounter. This is why creating training sessions that replicate these situations is so important in the development of a football player.

Secondly, once the player has the awareness to recognize distinct situations, they must be able to take advantage of them. At this point in their development is where their technical abilities will come into play. However, knowing what we know now about the requirements of such a complex tactical system, we can see the importance of never decontextualizing or separating technique from tactics. If you haven’t done so, I urge to read the post on Coaching in Context: Teaching and Tactics and Technique where I discuss why the two can never be separated or isolated.

Using positional play as a medium to teach technical aspects, it would be foolish to ask a player to perform specific technical actions without giving him a context or situation that they may encounter in the system. For example, the manner in which a player receives the ball depends entirely on the tactical intention in a specific area or time of a build-up. Applying this thinking to all technical actions, we arrive to the conclusion that technique will develop, and should be taught, with appropriate training exercises to produce circumstances from positional play.

Lastly, when developing the training session, it’s paramount to consider the age of the players. As Juan Antón states, “the pedagogic learning process should respect the biological, psychological, and sociological identity of the child or adolescent.” You wouldn’t give a six year old a copy of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet to improve their reading skills. The same idea applies to football. You’re not going to use Guardiola’s training session from Bayern Munich for your under 10 team.

Read: Child Psychology 101 for Every Youth Coach (Free PDFs)

There is a linear progression in the development of skills. Therefore, it is possible to create a linear sequence of fundamental skills which need to be mastered as the child develops cognitively, psycho-socially, and physically, as well as the development of technical abilities.

Let’s take a simple concept like dribbling to attract a defender (used to create numerical superiority). Cognitively, the player needs to have spatial awareness, a complete understanding of the purpose of their action within the context of the game, and in this case it’s to create numerical superiority with the objective of progressing up the pitch. Psycho-socially, the player should understand the relationship between him and his teammate to be able to connect with his teammate when the numerical advantage is present. Physically, the player must have speed, strength, resistance, and a combination of motor skills required for this kind of movement. Technically, the player should master dribbling with both feet at speed.

“There is nothing more marvelous than thinking of a new idea. There is nothing more magnificent than seeing a new idea working. There is nothing more useful than a new idea that serves your purpose.”

How can I help you?

Coaching Positional Play Online Course: Preview the first section here

Consulting Service: Set up your first session here

4-Week Game Model Development Workshop: Sign up here

4-Week Tactical Analysis Workshop: Sign up here

4-Week Training Session Development: Sign up here

Not ready to commit: Explore our training sessions, E-Books, future webinars, and past webinars.

Enjoyed the Positional Play Series? Want to enjoy it offline? Purchase the customised Positional Play Series mini book.